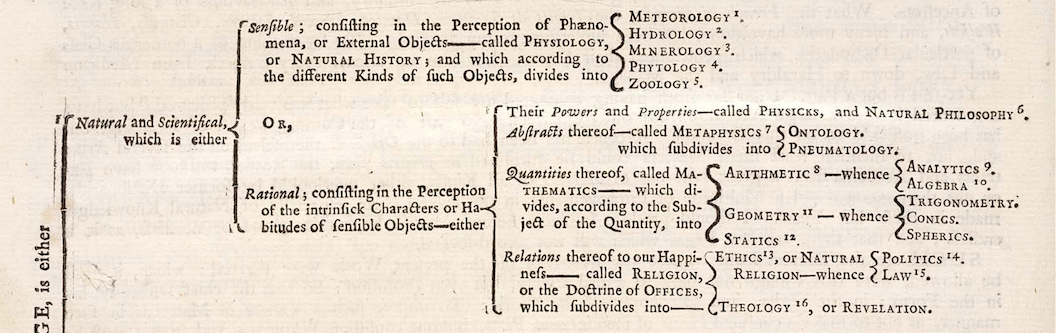

An arc of a circle is a part of the circumference thereof, less than a half, or semicircle—Such is AB (Tab. Geometry, fig. 27)

See CIRCLE and CIRCUMFERENCE.

The base or line that joins the two extremes of the arch is called the chord; and the perpendicular raised in the middle of that line,the size of the arch. See CHORD and SINE.

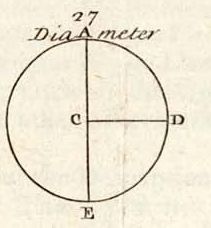

All angles are measured by arches—to know their quantity, an arch is described, having its center in the point of the angle. See ANGLE.

Every circle is supposed to be divided into 360 degrees; and an arch is estimated according to the number of those degrees it takes up.

Thus an arch is said to be of 30, of 80, of 100 degrees. See DEGREE.

Hence equal angles are such arches of the same or equal circles, as contain the same number of degrees. See EQUAL.

Hence in the same or equal circles, equal chords subtend equal arches. And hence, again, arches intercepted between parallel chords are equal.

A Radius, CE, fig.98,

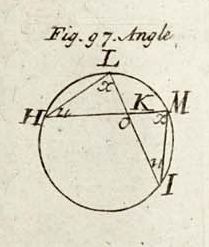

which bisects the chord AE also bisects segment EA and is perpendicular; thus, and we see parallel. And hence the problem, to bisect an ordinary arch is solved by me drawing a line AB perpendicular toSimilar Arches are those which contain the same number of degrees of unequal circles.

See Similar—Such are the arches AB and DE, fig. 87.

Two Radii being drawn from the center of two concentric circles; the two arches intercepted between them, bear the same ratio to their respective peripheries;and also the two sectors to the areas of their respective circles. See ANGLE. The distance of the center of gravity of an arch of a circle, from the center of the circle,is a third proportional to a third part of the periphery and the radius. See CENTER OF GRAVITY. For the sines, tangents, etc., of arches. See SINE, TANGENT, etc.

Arc in Astronomy—Diurnal Arc of the Sun, is part of a circle parallel to the equator, described by the Sun in his course between rising and setting. See Diurnal,Day, etc.

His Nocturnal Arch is of the same kind; except that it is described between his setting and rising. See NIGHT RISING, etc. The latitude and elevation of the pole are measured by an arch of the meridian; the longitude, by an arch of a parallel circle. See ELEVATION, LATITUDE, LONGITUDE, etc. Arc of Progression, or Direction, is an arch of the zodiac which a planet seems to pass over, when its motion is according to the order of the signs. See DIRECTION. The Arc of Retrogradation is an arch of the zodiac,described while a planet is retrograde, and moves contrary to the order of the signs. See RETROGRADATION.

Arc of Station. See Station and Stationary;Arc between the Centres is an arch, as A1 (Tab. Astronomy, fig. 35.) passing from the center of the Moon'sshadow, A, perpendicular to her orbit GH. See ECLIPSE.

If the aggregate of the arch between the centers A1,and the apparent semi-diameter of the moon, be equal tothe semi-diameter of the shadow; the eclipse will betotal without any duration: if less, total with some duration; and if greater, yet less than the sum of the semi-diameters of the moon and the shadow, partial—Arc of Vision is the sun’s depth below the horizon, at which a star, before hidden in his rays, begins to appear again. See POETICAL RISING.

Arc, in architecture, is a concave building, raised with a mold bent in form of the arch of a curve, and serving asthe inward support of any superstructure. See BUILDING.

An Arch, says Sir Henry Wotton, is nothing but a narrow or contracted vault; and a vault, a dilated arch. See VAULT.

Arches are used in large intercolumniations of spaciousbuildings; in porticos, both within and without temples; in public halls, as ceilings, the courts of palaces,cloisters, theaters, and amphitheaters. See PORTICO, THEATER, CEILING, etc.

They are also used as buttresses and counter-forts to support large walls laid deep in the earth, for foundationsof bridges and aqueducts, for triumphal arches, gates,windows, etc. See BUTTRESS, ARC-BOUTANT, etc.

Arches are either circular, elliptical, or straightCircular Arches are of three kinds, viz.—first, Semicircular, which make an exact semicircle, and have theircenter in the middle of the chord of the arch.

Secondly, Schemes, which are less than a semicircle, and consequently are flatter arches; containing some, 90 degrees,others 70, and others only 60. Thirdly, Arches of the third and fourth point, as some ofour workmen call them; though the Italians call them diterzo and quarto acuto, because they always meet in anacute angle at top. These consist of two arches of acircle ending in an angle at the top, and are drawnfrom the division of a chord into three or four parts, atpleasure. Of this kind are many of the arches in old Gothic buildings; but on account, both of their weaknessand unsightliness, they ought, according to Sir HenryWotton, to be forever excluded out of all buildings.

Elliptical Arches consist of a semi-ellipsis and wereformerly much used instead of mantle-trees in chimneys—These have commonly a keystone and chapitrels or imposts.

Straight Arches, are those whose upper and under edgesare straight; as in the others they are curved; and those twoedges also parallel, and the ends and joints all pointingtowards a center—These are principally used over windows, doors, etc. The Doctrine and Use of Arches is well delivered by Sir Henry Wotton, in the following Theorems.—First, all matter, unless impeded, tends to the center of the Earth in a perpendicular line. See DESCENT, GRAVITY, CENTRE, etc.

Secondly, all solid materials, such as bricks, stones, etc., in their ordinary rectangular form, if laid in numbers, one by the side of another, in a level row, and their extreme ones sustained between two supporters; those in the middle will necessarily sink, even by their own gravity, much more if pressed down by any superincumbent weight. To make them stand, therefore, either their figure or their position must be altered.

Thirdly, stones or other materials being figured cuneate, i.e., wedge-wise, broader above than below, and laid in a level row, with their two extremes supported as in the preceding theorem and pointing all to the same center; none of them can sink until the seat or buttments give way because they lack room in that position to descend perpendicularly. But this is but a weak structure, as the supporters are subject to too much impact, especially where the line is long; for which reason, the form of straight arches is seldom used, excepting over doors and windows, where the line is short. In order to fortify the work, therefore, we must not only change the figure of the materials but also their position.

Fourthly, if the materials be shaped wedge-wise and be disposed in the form of a circular arch, and pointing to some center; in this case, neither the pieces of the said arch can sink downwards for want of room to descend perpendicularly; nor can the supporters or buttments suffer so much violence as in the precedent flat form: for the convexity will always make the incumbent weight rest upon the supporters, rather than heave them outwards. Whence this corollary may be fairly deduced, that the securest of all the arches aforementioned is the semicircular; and of all vaults, the hemispherical.

Fifthly, as semicircular vaults, raised on the whole diameter, are the strongest; so those are the most beautiful, which keeping to the same height, are yet distended one-fourteenth part longer than the said diameter: which addition of width will contribute greatly to their beauty, without diminishing anything considerable of their strength. It is, however, to be observed, that according to geometrical strictness, to have the strongest arches, they must not be portions of circles, but of another curve, called the Catenary, whose nature is such that a number of spheres disposed in this form, will sustain each other, and form an arch. See CATENARIA.

Dr. Gregory even shows, that arches constructed in other curves only stand or sustain themselves by virtue of the catenaria contained in their thickness; so that were they made infinitely slender or thin, they must tumble of course; whereas the Catenaria, though infinitely slender, must stand, in regard no one point thereof tends downward more than any other. Philosophical Transactions, No. 231.

See further of the Theory under the Article Vault.

Arches are sustained by imposters. See IMPOSTS.

Arch is particularly used for the space between the two piers of a bridge. See PIER and BRIDGE.

The chief or master arch is that in the middle, which is widest, and usually highest, and the water under it deepest: being intended for the passage of boats or other vessels. We read of bridges in the East, which consist of 300 arches. Arch-Stone. See KEY-STONE.

Triumphal Arch, is a gate, or passage into a city, magnificently adorned with architecture, sculpture, inscriptions, etc., which being built of stone or marble, serves not only to adorn a triumph, at the return from a victorious expedition, but also to preserve the memory of the conqueror to posterity. See TRIUMPH.

The most celebrated triumphal arches, now remaining of antiquity, are those of Titus, of Septimius Severus, and of Constantine, at Rome.

Arch, in the Scripture sense. See ARCH.

Arch, or Arch, is also a term without any meaning of itself, but which becomes very significant in composition with other words: it heightens and exaggerates them; and has the force of a superlative, to show the greatest degree or eminence of anything.

Thus we say Arch-fool, Arch-rogue, etc., to express folly and knavery in the utmost degree.

Also Arch-Treasurer, Arch-Angel, Arch-Bishop, Arch-Heretic, etc., to denote such as have a pre-eminence over others.

The word is formed of the Greek ἀρχή, beginnings; whenceἄρχων, princeps, summus.

In English we usually, though to very ill purpose; the words wherewith joined, sounding much harsher on that score than would do were it preserved entire, as it is in most languages. See ANOMALOUS, CONTRACTION, etc.