ATTRACTION, or ATTRACTIVE FORCES in Physics, is a natural Power inherent in certain Bodies, whereby they act on other distant Bodies, and draw them towards themselves. See FORCE. This, the Peripatetics call the Motion of Attraction; and on many Occasions, Σύμπνοια; and produce various Instances where they suppose it to obtain.—Thus the Air, in Respiration, is taken in, according to them, by Attraction, or Suction; so is the Smoke through a Pipe of Tobacco; and the Milk out of the Mother's Breasts: Thus also it is that the Blood and Humours rise in a Cupping-Glass, Water in a Pump, and Smoke in Chimneys; so Vapours and Exhalations are attracted by the Sun; Iron by the Magnet, Straws by Amber, and electrical Bodies, etc. See SUCTION. But the later Philosophers generally explode the Notion of Attraction; asserting, that a Body cannot act where it is not; and that all Motion is performed by mere Impulsion—Accordingly, most of the Effects which the Ancients attributed to this unknown Power of Attraction, the Moderns have discovered to be owing to more sensible and obvious Causes; particularly the Pressure of the Air. See AIR and PRESSURE. To this are the Phenomena of Inspiration, Smoking, Sucking, Cupping-Glasses, Pumps, Vapours, Exhalations, etc. See RESPIRATION, SUCTION, PUMP, CUPPING-GLASS, VAPOUR, SMOKE, EVAPORATION, etc. For the Phenomena of magnetical and electrical Attraction, see Magnetism and Electricity. The Power opposite to Attraction is called Repulsion; which is also argued to have some Place in natural Things. See REPULSION.

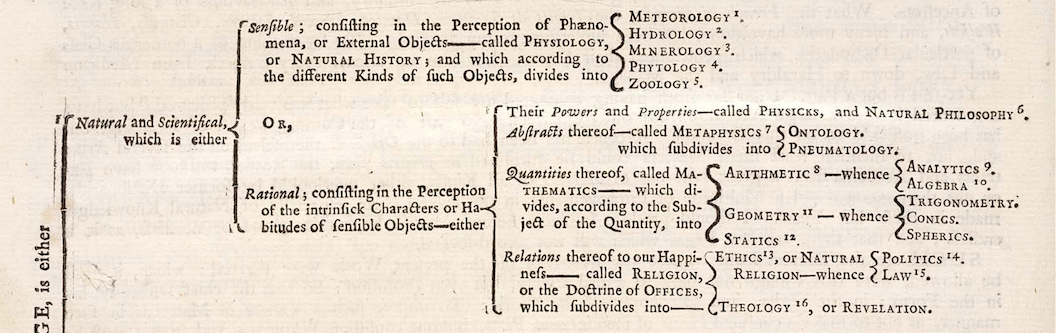

ATTRACTION, or ATTRACTIVE POWER; in the Newtonian Philosophy, is a Power or Principle, whereby all Bodies, and the Particles.

PARTICLES OF ALL BODIES, mutually tend towards each other—Or, more justly, Attraction is the effect of such power, whereby every particle of matter tends towards every other particle. See MATTER and PARTICLE.

ATTRACTION, its laws, phenomena, etc. make the great hinge of Sir Isaac Newton's philosophy. See NEWTONIAN PHILOSOPHY. It must be observed, that though the great author makes use of the word attraction, in common with the school philosophers; yet he very studiously distinguishes between the ideas.—The ancient attraction was a kind of quality inherent in certain bodies themselves; and arising from their particular or specific forms. See QUALITY and FORM. The Newtonian attraction is a more indefinite principle; denoting, not any particular kind or manner of action, nor the physical cause of such action; but only a tendency in the general, a conatus accedendi, to whatever cause, physical or metaphysical, such effect be owing; whether to a power inherent in the bodies themselves, or to the impulse of an external agent. Accordingly, the great author, in his Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica, notes, "that he uses the words attraction, impulse, and propensity to the centre, indifferently; and cautions the reader not to imagine that by attraction he expresses the modus of the action, or the efficient cause thereof; as if there were any proper powers in the centres, which in reality are only mathematical points; or, as if centres could attract." Lib. I. p. 5.—So, he "considers centripetal powers as attractions; though, physically speaking, it were perhaps more just to call them impulses." Ib. p. 147. He adds, "that what he calls attraction may possibly be effected by impulse, though not a common or corporeal impulse; or in some other manner unknown to us." Optics, p. 322.

ATTRACTION, if considered as a quality arising from the specific forms of bodies, ought, together with sympathy, antipathy, and the whole tribe of occult qualities, to be exploded. See OCCULT QUALITY. But when we have set these aside, there will remain innumerable phenomena of nature, and particularly the gravity or weight of bodies, or their tendency to a centre, which argue a principle of action seemingly distinct from impulse; where, at least, there is no sensible impulsion concerned. Nay, what is more, this action, in some respects, differs from all impulsion we know of; impulse being always found to act in proportion to the surfaces of bodies; whereas gravity acts according to their solid content, and consequently must arise from some cause that penetrates or pervades the whole substance thereof.—This unknown principle (unknown we mean in respect of its cause, for its phenomena and effects are most notorious) with all the species and modifications thereof, we call attraction; which is a general name, under which all mutual tendencies, where no physical impulse appears, and which cannot, therefore, be accounted for from any known laws of nature, may be ranged.

And hence arise divers kinds of attractions; as, gravity, magnetism, electricity, etc. which are so many different principles, acting by different laws; and only agreeing in this, that we do not see any physical causes thereof; but that, as to our senses, they may really arise from some power or efficacy in such bodies, whereby they are enabled to act, even upon distant bodies; though our reason absolutely disallows of any such action.

ATTRACTION may be divided, with respect to the law it observes, into two kinds.—1° That which extends to a sensible distance—Such are the attraction of gravity, found in all bodies; and the attractions of magnetism and electricity, found in particular bodies.—The several laws and phenomena of each, see under their respective articles, GRAVITY, MAGNETISM, and ELECTRICITY. The attraction of gravity, called also among mathematicians, the centripetal force, is one of the greatest and most universal principles in all nature.—We see and feel it operate on bodies near the earth. See WEIGHT.—And find, by observation, that the same power (i.e. a power which acts in the same manner, and by the same rules; viz. always proportionally to the quantities of matter, and as the squares of the distances) does also obtain in the moon, and the other planets, primary and secondary, as well as the comets: and even that this is the very power whereby they are all retained in their orbits, etc. And hence, as gravity is found in all the bodies which come under our observation, it is easily inferred, by one of the settled rules of philosophizing, that it obtains in all others; and as it is found to be as the quantity of matter in each body, it must be in every particle thereof; and hence every particle in nature is proved to attract every other particle, etc. See the demonstration hereof laid down at large, with the application of the principle to the system of motions, under the articles, NEWTONIAN PHILOSOPHY, SUN, MOON, PLANET, COMET, SATELLITE, CENTRIPETAL, CENTRIFUGAL, etc.

From this attraction arises all the motion, and consequently all the mutation, in the great world.—By this, heavy bodies descend, and light ones ascend; by this projectiles are directed, vapours and exhalations rise, and rains, etc. fall. By this rivers glide, the air presses, the ocean swells, etc. See MOTION, DESCENT, ASCENT, PROJECTILE, VAPOUR, RAIN, RIVER, TIDE, AIR, ATMOSPHERE, etc.

In effect, the Motions arising from this Principle make the subject of that extensive branch of Mathematics, called Mechanics, or Statics; with the parts or appendages thereof, Hydrostatics, Pneumatics, etc. See MECHANICS, STATICS, HYDROSTATICS, PNEUMATICS. See also MATHEMATICS, PHILOSOPHY, etc.

2°. That which does not extend to sensible distances—Such is found to obtain in the minute particles whereof bodies are composed, which attract each other at, or extremely near the point of contact; with a force much superior to that of gravity; but which at any distance therefrom decreases much faster than the power of gravity.—This power, a late ingenious author chooses to call the Attraction of Cohesion; as being that whereby the atoms or insensible particles of bodies are united into sensible masses. See COHESION, ATOM, PARTICLE, etc.

This latter kind of Attraction owns Sir Isaac Newton for its discoverer; as the former does, its improver.—The laws of motion, percussion, etc., in sensible bodies under various circumstances, as falling, projected, etc., as ascertained by the later philosophers, do not reach to those more remote, intestine motions of the component particles of the same bodies, whereon the changes of the texture, color, properties, etc. of bodies depend: So that our philosophy, if only founded on the principle of gravitation, and carried so far as that would lead us, would necessarily be very deficient. See LIGHT, COLOR, etc.

But, beside the common laws of sensible masses, the minute parts they are composed of, are found subject to some others, which have been but lately taken notice of, and are yet very imperfectly known. Sir Isaac Newton, to whose happy penetration we owe the hint, contents himself to establish, that there are such motions in the minima naturae, and that they flow from certain powers or forces, not reducible to any of those in the great world.—In virtue of these powers, he shows, “that the small particles act on one another even at a distance; and that many of the phenomena of nature are the result thereof: Sensible bodies, we have already observed, act on one another divers ways; and as we thus perceive the tenor and course of nature, it appears highly probable that there may be other powers of the like kind; nature being very uniform and consistent with herself. —Those just mentioned, reach to sensible distances, and so have been observed by vulgar eyes: But there may be others, which reach to such small distances, as have hitherto escaped observation; and ‘tis probable electricity may reach to such distances, even without being excited by friction.”The great author just mentioned, proceeds to confirm the reality of these suspicions from a great number of phenomena and experiments, which plainly argue such powers and actions between the particles, e.g. of salts and water, oil of vitriol and water, aqua fortis and iron, spirit of vitriol and saltpetre.—He also shows, that these powers, etc., are unequally strong between different bodies; stronger, e.g., between the particles of salt of tartar and those of aqua fortis, than those of silver; between aqua fortis and lapis calaminaris, than iron; between iron than copper, copper than silver, or mercury. So spirit of vitriol acts on water, but more on iron or copper, etc.

The other experiments which countenance the existence of such a principle of attraction in the particles of matter are innumerable; many of them the reader will find enumerated under the articles Matter, Acid, Salt, Menstruum, etc.

These actions, in virtue whereof the particles of the bodies above mentioned tend toward each other, the author calls by a general, indefinite name, Attraction, which is equally applicable to all actions, whereby distant bodies tend towards one another, whether by impulse, or by any other more latent power: And from hence accounts for an infinity of phenomena, otherwise inexplicable, to which the principle of gravity is insufficient.—Such are cohesion, dissolution, coagulation, crystallization, the ascent of fluids in capillary tubes, animal secretion, fluidity, fixity, fermentation, etc. See the respective articles, Cohesion, Dissolution, Crystallization, Ascent, Secretion, Sphericity, Fixity, Fermentation, etc.

“Thus,” adds our immortal author, “will nature be found very conformable to herself, and very simple; performing all the great motions of the heavenly bodies, by the attraction of gravity, which intercedes those bodies, and almost all the small ones of their parts, by some other attractive power diffused through the particles thereof.—Without such principles, there never would have been any motion in the world; and without the continuance thereof, motion would soon perish, there being otherwise a great decrease or diminution thereof, which is only supplied by these active principles.” Opticks, p. 373.

We need not say how unjust it is in the generality of foreign philosophers, to declare against a principle which furnishes so beautiful a view; for no other reason but because we cannot conceive how a body should act on another at a distance.

'Tis certain, Philosophy allows of no Action but what is by immediate Contact and Impulsion:(for how can a Body exert any active Power there, where it does not exist? To suppose this of any thing, even the supreme Being himself, would perhaps imply a Contradiction.) Yet we see Effects without seeing any such Impulse; and where there are Effects, we can easily infer there are Causes, whether we see them or no. But a Man may consider such Effects, without entering into the Consideration of the Causes; as, indeed, it seems the Business of a Philosopher to do: For to exclude a Number of Phenomena which we do see, will be to leave a great Chasm in the History of Nature; and to argue about Actions which we do not see, will be to build Castles in the Air—It follows, therefore, that the Phenomena of Attraction, are Matter of physical Consideration, and as such entitled to a Share in a System of Physics; but that the Cause thereof will only become so when they become sensible; i.e. when they appear to be the Effects of some other higher Causes, (for a Cause is no otherwise seen than as it itself is an Effect, so that the first Cause must from the Nature of things be invisible.) We are therefore at Liberty to suppose the Causes of Attractions what we please, without any Injury to the Effects—The illustrious Author himself seems a little irresolute as to the Cause; inclining, sometimes, to attribute Gravity to the Action of an immaterial Cause, Opticks, p. 343. and sometimes to that of a material one, Ib. p. 325. In his Philosophy, the Research into Causes is the last thing; and never comes in turn till the Laws and Phenomena of the Effect be settled; it being to these Phenomena that the Cause is to be accommodated.—The Cause even of any, the grossest, and most sensible Action is not adequately known: How Impulse or Percussion itself works its Effect, i.e. how Motion is communicated by Body to Body, confounds the deepest Philosophers; yet is Impulse received not only into Philosophy, but into Mathematics; and accordingly the Laws and Phenomena of its Effects, make the greatest Part of common Mechanics. See PERCUSSION, and COMMUNICATION OF MOTION. The other Species of Attraction, therefore, when their Phenomena are sufficiently ascertained, have the same Title to be promoted from physical to mathematical Considerations; and this, without any previous Inquiry into their Causes, which our Conceptions may not be proportionate to: Let their Causes be occult, as all Causes ever will be; so as their Effects, which alone immediately concern us, be but apparent. See CAUSE. Our noble Countryman, then, far from adulterating Philosophy with any thing Foreign, or Metaphysical; as many have represented him; has the Glory of opening a new Source of sublimer Mechanics, which, duly cultivated, might be of infinitely more Extent than all the Mechanics yet known: 'Tis hence alone we must expect to learn the manner of the Changes, Productions, Generations, Corruptions, etc. of natural things; with all that Scene of Wonders opened to us by the Operations of Chemistry. See GENERATION, CORRUPTION, OPERATION, CHEMISTRY, etc. Some of our own Countrymen have prosecuted the Discovery with laudable Zeal: Dr. Keil particularly, has endeavoured to deduce some of the Laws of this new Action, and applied them to solve divers of the more general Phenomena of Bodies, as Cohesion, Fluidity, Elasticity, Softness, Fermentation, Coagulation, etc. And Dr. Friend seconding him, has made a further Application of the same Principles, to account at once, for almost all the Phenomena that Chemistry presents—So that the new Mechanics should seem already raised to a complete Science, and nothing can now turn up, but we have an immediate Solution of, from the attractive Force. But this seems a little too precipitate; a Principle so fertile, should have been further explored; its particular Laws, Limits, more industriously detected and laid down, ere we had gone to Application.—Attraction, in the gross, is so complex a thing, that it may solve a thousand different things alike: The Notion is but one Degree more simple and precise, than Action itself; and till more of its Properties are ascertained, it were better to apply it less, and study it more. A Specimen of the extent of the Principle, and the manner of applying it, we shall here subjoin the principal Laws and Conditions thereof; as settled by Sir Isaac Newton, Dr. Keil, Dr. Friend, Dr. Morgan, etc.

Theor. I. Besides that attractive Power whereby the Planets and Comets are retained in their Orbits; there is another, by which the several Particles whereof Bodies consist, attract, and are mutually attracted by, each other; which Power decreases in more than a duplicate Ratio of the Increase of the Distance.

This Theorem we have already observed, is demonstrable from a great Number of Phenomena.—We shall here only mention a few easy and obvious ones; as, the Spherical Figure, assumed by the Drops of Fluids; which can only arise from such Principle: The uniting and incorporating of two Spherules of Quicksilver into one, upon the first touch, or extremely near approach of their Surfaces: The rising of Water up the Sides of a Glass Bubble immerged therein, higher than the Level of the other Water, or of Mercury up a Sphere of Iron, or the like.

See SPHERICITY, DROP, etc.

As to the Law of this Attraction, it is not yet determined; only this we know in the general, that the force, in receding from the Point of Contact, is diminished in a greater Proportion than that of the duplicate Ratio of the Distances, which is the Law of Gravity. For if the Diminution were only in such duplicate Ratio, the Attraction at any small assignable Distance would be nearly the same as at the Point of Contact; whereas Experience teaches, that this Attraction almost vanishes and ceases to have any Effect, at the smallest assignable Distance. But whether to fix on a triplicate, quadruplicate, or some other Proportion to the increasing Distances, is not ascertained by Experiment.

II. The Quantity of Attraction in all Bodies, is exactly proportional to the Quantity of Matter in the attracting Body; as being in reality the Result or Sum of the united Forces of the Attractions of all those single Particles of which it is composed; or, in other Words, Attraction in all Bodies is, ceteris paribus, as their Solidities. Hence, 1°. At equal Distances the Attractions of homogeneal Spheres will be as their Magnitudes.—And, 2°. At any Distance whatever, the Attraction is as the Sphere divided by the Square of the Distance. This Law, it must be noted, only holds in respect of Atoms; or the smallest constituent Particles, sometimes call’d Particles of the last Composition, and not of Corpuscles or Compositions made up of these; for they may be so put together, as that the most solid Corpuscles may form the lightest Particles; i.e. the unfitness of their Surfaces for intimate Contact, may occasion such great Interstices as will make their Bulks large in Proportion to their Matter.

III. If a Body consist of Particles, every one whereof has an attractive Power decreasing in a triplicate, or more than a triplicate Ratio of their Distances; the Force wherewith a Particle is attracted by that Body in the Point of Contact, or at an infinitely little Distance from the Contact, will be infinitely greater than if that Particle were placed at a given Distance from the Body. See INFINITE.

IV. Upon the same Supposition, if the attractive Force at any assignable Distance, have a finite Ratio to its Gravity; this Force in the Point of Contact, or at an infinitely small Distance, will be infinitely greater than its Power of Gravity.

V. But if in the Point of Contact the attractive Force of Bodies have a finite Ratio to their Gravity; this Force in any assignable Distance is infinitely less than the Power of Gravity, and therefore ceases.

VI. The attractive Force of every Particle of Matter in the Point of Contact, almost infinitely exceeds the Power of Gravity, but is not infinitely greater than that Power; and therefore in a given Distance, the attractive Force will vanish. This attractive Power, therefore, thus superadded to Matter, only extends to Spaces extremely minute, and vanishes in greater Distances; whence, the Motion of the heavenly Bodies, which are at prodigious Distance from each other, cannot at all be disturbed by it, but will continually go on as if there were no such Power in Bodies. Where this attracting Power ceases; there, according to Sir Isaac Newton, does a repelling Power commence; or rather, the attracting does, thence forward become a repelling Power. See REPELLING POWER.

VII. Supposing a Corpuscle to touch any Body, the Force whereby that Corpuscle is impell’d, that is, the Force with which it coheres to that Body, will be proportionable to the Quantity of Contact: For the Parts farther remov’d from the Point of Contact, contribute nothing towards its Cohesion. Hence, according to the Difference in the Contact of Particles, there will be different Degrees of Cohesion: But the Powers of Cohesion are greatest when the touching Surfaces are Planes; in which case, ceteris paribus, the Force by which one Corpuscle adheres to others, will be as the Parts of the touching Surfaces. Hence it appears why two perfectly polish’d Marbles, join’d together by their plane Surfaces, cannot be forced asunder, but by a Weight which much exceeds that of the incumbent Air. Hence also may be drawn a Solution of that famous Problem concerning the Cohesion of the Parts of Matter. See COHESION.

VIII. The Power of Attraction in the small Particles increases, as the Bulk and Weight of the Particles diminishes. For, the Force only acting at or near the Point of Contact, the Momentum must be as the Quantity of Contact, that is, as the Density of the Particles, and the Largeness of their Surfaces; But the Surfaces of Bodies increase or decrease as the Squares, and the Solidities as the Cubes of the Diameter. Consequently, the smallest Particles having the largest Surfaces in proportion to their Solidities, are capable of more Contact, etc. Those Corpuscles are most easily separated from one another, whose Contacts are the fewest and the least, as in Spheres infinitely small. Hence we have the Cause of Fluidity. See FLUIDITY, WATER, etc.

IX. The Force whereby any Corpuscle is drawn to another nearly adjacent Body, suffers no Change in its Quantity, let the Matter of the attracting Body be increased or diminished; supposing the same Density to remain in the Body, and the Distance of the Corpuscle to continue the same.

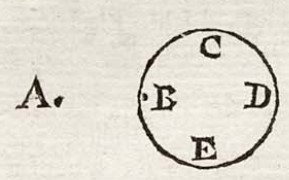

For since the attractive Powers of Particles are diffus’d only through the smallest Spaces; 'tis manifest that the remoter Parts at CD and E contribute nothing towards attracting the Corpuscle: And therefore the Corpuscle will be attracted with the same Force towards B, whether these Parts remain or be taken away; or, lastly, whether others be added to them. Hence, Particles will have different attractive Forces, according to their different Structure and Composition, thus a Particle perforated will not attract so strongly as if entire. So, again, the different Figures into which a Particle is form’d, will occasion a diversity of Power: Thus a Sphere will attract more than a Cone, Cylinder, etc.

X. Suppose a Body of such a Texture as that the Particles of the last Composition, by an external Force, such as a Weight compressing them, or an Impulse given by another Body, may be a little removed from their original Contact, but so as not to acquire new ones; the Particles by their attractive Force tending to one another, will soon return to their original Contacts.—But when the same Contacts and Positions of the Particles which compose any Body, return; the same Figure of the Body will also be restor’d: And therefore Bodies which have lost their original Figures, may recover them by Attraction. Hence appears the Cause of Elasticity—For, where the contiguous Particles of a Body have by any external Violence been forc’d from their former Points of Contact, to extremely small Distances; as soon as that Force is taken off; the separated Particles must return to their former Contact: By which means the Body will resume its Figure, etc. See ELASTICITY.

XI. But if the Texture of a Body be such that the Particles by an impressed Force being removed from their Contacts, come immediately into others of the same Degree, that Body cannot restore itself to its original Figure. Hence we understand what Texture that is wherein the Softness of Bodies consists. See SOFTNESS.

XII. The Bulk of a Body heavier than Water, may be so far diminished, that it shall remain suspended in Water, without descending by its own Gravity. See SPECIFIC GRAVITY. Hence it appears why saline, metallic, and other such-like Particles, when reduc’d to small Dimensions, are suspended in their Menstruums. See MENSTRUUM.

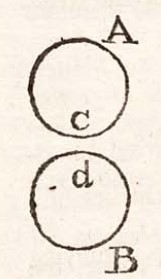

XIII. Greater Bodies approach one another with a less Velocity than smaller—

For the Force with which two Bodies A and B approach, resides only in the nearest Particles; the more remote having nothing to do therein. No greater Force, therefore, will be apply’d to move the Bodies A and B, than to move the Particles c and d; but the Velocities of Bodies mov’d by the same Force are in a reciprocal Ratio of the Bodies: Wherefore the Velocity with which the Body A tends towards B, is to the Velocity with which the Particle c detach’d from the Body would tend towards the same B, as the Particle c is to the Body B; consequently the Velocity of the Body A is much less than wou’d be the Velocity of the Particle c detach’d from the Body. Hence it is that the Motion of large Bodies is naturally so slow and languid, that an ambient Fluid and other circumjacent Bodies generally retard them; whilst the lesser go on more briskly, and produce a greater number of Effects: So much greater is the attractive Energy in smaller Bodies than in the larger.—Hence again appears the Reason of that chemical Axiom; Salts don’t act till they are dissolv'd.

XIV. If a Corpuscle placed in a Fluid be equally attracted every way by the circumambient Particles, no Motion of the Corpuscle will ensue.—But if it be attracted by some Particles more than others, it will tend to that part where the Attraction is the greatest; and the Motion produc’d will correspond to the Inequality of the Attraction, viz. the greater the Inequality, the greater the Motion, and vice versa.

XV. Corpuscles floating in a Fluid, and attracting each other more than the Particles of the Fluid that lie between them, will force away the Particles of the Fluid, and rush to one another with a Force equal to that by which their mutual Attraction exceeds that of the Particles of the Fluid.

XVI. If a Body be immerged in a Fluid whose Parts more strongly attract the Particles of the Body than they do one another; and if there be a number of Pores or Interstices in the Body pervious to the Particles of the Fluid; the Fluid will immediately diffuse itself through those Pores. And if the Connexion of the Parts of the Body be not so strong, but that it may be overcome by the Force of the Particles rushing within it; there will be a Dissolution of the Body. See DISSOLUTION. Hence, for a Menstruum to be able to dissolve any given Body, there are three things requir’d.—1°. That the Parts of the Body attract the Particles of the Menstruum more strongly than these attract each other.

2°. That the Body have Pores or Interstices open and pervious to the Particles of the Menstruum.

3°. That the Cohesion of the Particles which constitute the Body, be not strong enough to resist the Irruption of the Particles of the Menstruum. See MENSTRUUM.

XVII. Salts are Bodies endued with a great attractive Force, though among them are interspersed many Interstices, which lie open to the Particles of Water; these are therefore strongly attracted by those saline Particles, so that they forcibly rush into them, separate their Contacts, and dissolve the Contexture of the Salts. See SALT.

XVIII. If the Corpuscles be more attracted by the Particles of the Fluid than by each other; they will recede from each other, and be diffused through the whole Fluid. Thus, if a little Salt be dissolved in a deal of Water, the Particles of the Salt, though specifically heavier than Water, will evenly diffuse themselves through the whole Water; so as to make it as saline at Top as Bottom.—Does not this imply that the Parts of the Salt have a centrifugal, or repulsive Force, by which they fly from one another; or rather, that they attract the Water more strongly than they do one another? For as all things ascend in Water which are less attracted than Water by the Gravity of the Earth, so all the Particles of Salt floating in Water, which are less attracted by any Particle of Salt, than Water is, must recede from the Particle, and give way to the more attracted Water. Newt. Opt. p. 363.

XIX. Corpuscles, or little Bodies swimming in a Fluid, and tending towards each other; if they be supposed elastic, will fly back again after their Congress, till striking on other Corpuscles, they be again reflected towards the first; whence will arise innumerable other Conflicts with other Corpuscles, and a continued Series of Percussions and Reboundings—But, by the attractive Power, the Velocity of such Corpuscles will be continually increased; so that the intestine Motion of the Parts will at length become evident to Sense. See INTESTINE MOTION. Add, that in proportion, as the Corpuscles attract each other with a greater or less Force, and as their Elasticity is in a greater or less Degree, their Motions will be different, and become sensible at various Times, and in various Degrees.

XX. If Corpuscles that attract each other happen mutually to touch, there will not arise any Motion, because they cannot come nearer. If they be placed at a very little Distance from each other, a Motion will arise; but if further removed, the Force wherewith they attract each other, will not exceed that wherewith they attract the Particles of the intermediate Fluid, and therefore no Motion will be produced. On these Principles depend all the Phenomena of Fermentation and Ebullition. See FERMENTATION and EBULLITION. Hence appears the Reason why Oil of Vitriol, when a little Water is poured on it, works and grows hot: For, the saline Corpuscles are a little disjoined from their mutual Contact, by the infused Water; whence, as they attract each other more strongly than they do the Particles of Water, and as they are not equally attracted on every side, there must of necessity arise a Motion. See VITRIOL. Hence also appears the Reason of that uncommon Ebullition occasioned by adding Steel-filings to the foresaid Mixture. For the Particles of Steel are extremely elastic; whence there must arise a very strong Reflection. Hence also we see the Reason why some Menstruums act more strongly, and dissolve Bodies sooner, when diluted with Water.

XXI. If Corpuscles mutually attracting each other have no elastic Power, they will not be reflected back from each other, but will form Congeries, or little Masses; whence a Coagulum will arise. See COAGULATION. If the Gravity of the Particles thus amassed, exceed the Gravity of the Fluid, a Precipitation will succeed—Precipitation may also arise from an Increase or Diminution of the Gravity of the Menstruum wherein the Corpuscles are immerged. See PRECIPITATION.

XXII. If Corpuscles swimming in a Fluid, and mutually attracting each other, have such a Figure, as that in some given Parts they have a greater attractive Power than in others, and their Contact greater in those Parts than in others; those Corpuscles will unite into Bodies with given Figures; and thence will arise Crystallization. See CRYSTALLIZATION.

XXIII. Particles immerged in a Fluid moved with a swift or a slow progressive Motion, will attract each other in the same Manner as if the Fluid were at rest; but if all the Parts of the Fluid do not move equally, the Attractions will be disturbed. Hence it is that Salts will not crystallize till the Water wherein they are dissolved is cold.

XXIV. If between two Particles of a Fluid there happen to be a Corpuscle whose two opposite Sides have a strong attractive Power, that intermediate Corpuscle will agglutinate or fasten the Particles of the Fluid to itself—And several such Corpuscles diffused through the Fluid, will fix all its Particles into a firm Body; and the Fluid will be froze or reduced into Ice. See FREEZING.

XXV. If a Body emit a great Quantity of Effluvia whose attractive Powers are very strong; as those Effluvia approach any other very light Body, their attractive Powers will overcome the Gravity of that Body, and the Effluvia will draw it towards themselves:And as the Effluvia are closer and more copious at little Distances from the emitting Body, than at greater; the light Body will be continually drawn towards the denser Effluvia, till such time as it comes to adhere to the emitting Body itself.

And hence most of the Phenomena of Electricity may be accounted. See ELECTRICITY.